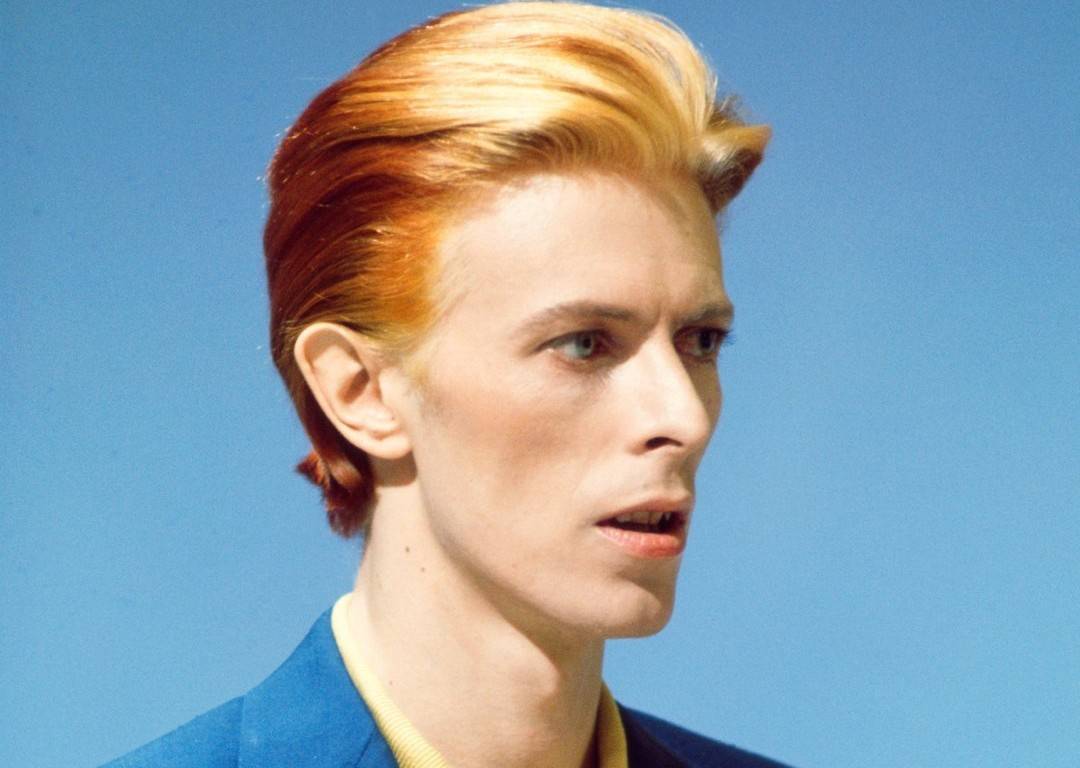

DAVID BOWIE: HOW A DEEPLY FLAWED PERSON CHANGED CULTURE, GENDER AND SEXUALITY

By Jonno Revanche

I was 12 years old when I first became aware of David Bowie, the human.

But it feels wrong to call him just that, because almost everyone viewed him as something else: a slightly mystical, deeply intelligent half-alien entity that occupied a space somewhere between the parchment of pop culture and an alternative musical world. He was a fixture in my mind and a source of great influence for, challenging everything I knew about life and acceptability. And he was introduced to me by best friend at the time, a girl who wore broken glasses, rainbow mittens, op shopped scarves and leg warmers – and who had started puberty before anyone else in our year.

As it stood, she towered over almost everyone else (even the boys, who were mostly terrified of her) including me, but she loved me and defended me fiercely. It was the first time I had felt love specifically like that, like we had a responsibility to each other.

It was a love affair that entrenched my admiration of the Thin White Duke – although I think I was more an admiration for his message and what he meant to people, rather than just him as a person.

For many people, I imagine this will be the case, and I want to emphasise this because he was not like other celebrities and that will be relevant to what I’m typing out. He seemed uncomfortable initially to me, I think, because he represented so many things I was beginning to hide in myself. A chameleonic gender fluidity. An anarchistic sexuality and style. A genuine detachment and disenchantment from the physical world. My initial feelings toward him mirrored my mothers feelings towards my best friend. My mum regarded her as a “little bit weird” and potentially dangerous. My grade 7 teacher told me that he didn’t understand why I hung out with her, and that I should consider choosing “more appropriate company.”

Of course, these things made me love her even more.

As we went out separate ways and attended different high schools, my love of David Bowie only heightened. I bought CDs of his for $10 each and listened to them alone in my bedroom. It felt like a kind of secret rebellion. I would listen to his music in quiet places – walking home at night, and on my own, riding home on the bus from the eastern suburbs in Adelaide to the northern suburbs, coming home to an empty house.

For many “queer” people, and gender non-conforming or trans people, Bowie was one of their first examples of somebody fucking with gender in a way that was openly unapologetic and celebratory. He encouraged open dialogues about performance and gender presentation that other performers may have done bettered in the wake of his influence, but he was always one of the most visible. I cannot stress how many people this may have saved. Even if you’re not someone who was queer, Bowie’s message was all about maximalism and full embrace of the self, and I think that’s why the outpouring of grief is so strong.

Many people felt like he personally guided them into self acceptance and adulthood.

However, upon his death there was an equally strong reaction of grief: this was a different type though. It was because it had been unearthed that during his 20s, Bowie had reportedly slept with a 13 year old groupie. There is footage of the young Lori Maddox excitedly talking about losing her virginity to him and it is a grim video to watch, for many reasons.

Mainly, it is clear she had no idea how she would feel about it later on, how exploited she might feel by someone so powerful. For many, this will be devastating to hear because they thought he could do no wrong. But consider also the many young women and CSA survivors who will feel devastated about this for other reasons.

I think policing someone’s memories and grief for what Bowie’s music did to them is equally as horrible, because these people might not be grieving for him as a person. They may be grieving for their younger self, someone who overcame mental illness or bullying because of him, and those will already be painful memories. Nobody knows Bowie outside of the people or family that actually met him in person. And we are dealing with projections: ideas of what we think someone is truly like. Now, after learning about this and coming to terms with the reality of idolisation – I want to be the person that people thought Bowie was.

Because although Bowie’s interactions with gender fucking, queerness and sexuality faded over time, those things are real to me, and I can be the person I wanted to see when I was younger.

It is almost impossible for me to remove his music from my memories of growing up and of reaching a place where I could be myself. Even though I try, it would be disingenuous to say those things don’t matter to me.

When I was 17, five years after Michelle and I parted ways, I was lurking her myspace and felt my chest growing cold. I started seeing words that represented something, but my brain wasn’t processing fast enough, and eventually the shock subsided and I realised they were obituaries.

Michelle, someone who had struggled with family problems, self harm and depression since a young age, had taken her whole life. And I was sent into a spiral. Because although we had drifted a bit, we were just as in love with each other as we were in primary school. Something that was so rooted in vulnerability and trust was immediately taken from me.

I felt like I had abandoned her. The many months that followed were filled with music, tears, regrets, visits to a school counsellor and a cold and white room. The music I listened to was the same as the stuff she gave me when I was in primary school and those she had given me when I was 13. And my memories of that time were so fixed to Bowie, it feels painful to me that people on the internet are now calling me an asshole for thinking back to those times and writing about it.

I realised that men, no matter what kind of men, always need to be held accountable for their power. Bowie seemed like the only exception to me. He was the one man that could resist the hyper-masculinity of the everyday, and indeed the rock world, and prove that there could be amazing men in the world. But it’s my fault for idolising him and removing him of all his agency, when there was a real woman who was changed by his actions.

So many celebrities have broken my heart over the years, but it just shows that we need to not let men off the hook and idolise them, no matter what our initial impressions of them are. We need to instead see them as human beings worthy of respect and love, but who are profoundly and exceptionally human. No one will ever transcend human flaw or truly, fully embody the things you project on to them.

Ever.

If you hold people to unearthly standards you will always end up disappointed. A pedestal is not a home and is no way to keep someone. David Bowie took advantage of this pedestal and godliness to do some horrible things – that makes me think of what this culture can enable.

Love is not a finite resource. Despite what people on the internet are saying, you can care about two things at once: the statutory rape of Lori Maddox and your own memories that are linked to David Bowie. Certainly, they clash – but they are not mutually exclusive. In fact, I hope we can move forward into the future and not blame people who are already grieving and in pain. I hope dialogues about consent, statutory rape and powerful men will become as ever-present now as ever, because I too have been exploited and assaulted by men who were more powerful than me, and I never felt like I could speak up. I know many survivors on both sides of the fence. Think about the many survivors who are feeling old wounds open up today as they realise abusive men will often get away with what they’ve done and continue to be celebrated. Think of how they will feel when you uncritically celebrate Bowie.

Neither reaction is “wrong.” But if we move with care and consideration, we can create space to accommodate all of us.