Why it’s complicated being gay on Anzac Day

By Samuel Leighton-Dore

Before getting into the drunken swing of the Anzac Day long-weekend I have a small confession to make. Ever since I was a seven-year-old standing awkwardly for a live performance of the Last Post in school assembly, Anzac Day has made me feel a little uncomfortable.

It’s not that I have a problem with the notion of Anzac values – but I’ve certainly grown to take issue with our selective political memory and continued invocation of what those Anzac values were. Now, before you jump down my throat for disrespecting our nation’s history (a patriotic defensiveness rarely applied in the same way to our Indigenous history) – that’s not what I’m trying to do.

In fact, I’m attempting the opposite.

Well, Anzac Day has been marred by homophobia since its inception. Back in 1982, a group of five gay men attended Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance to lay a wreath. As they climbed the steps, Victorian RSL President Bruce Ruxton reportedly called out “Stop those men!” and, together with the Shrine guard and the Shrine commissionaire, blocked the group and escorted them from the premises.

But these weren’t just any gay men, they were five gay ex-servicemen; members of the now-disbanded Gay Ex-Services Association (GESA).

Of course, historians have since found evidence of countless gay men serving in WWI, with records of soldiers being convicted for “buggery” or tabloids reporting gay soldiers roaming the city streets. Once discovered, these men faced the awful choice of being publicly outed and unceremoniously stripped of their badges, or quietly resigning from the Australian Defense Force and disappearing without a trace.

While certain steps have been taken in recent years to finally address these cruel injustices (during last year’s Mardi Gras, representatives of the Defence Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Information Service lay a wreath at the Shrine in Melbourne), the homophobic and discriminatory undertone to our Anzac tradition continues largely unabated.

On April 25th of 2011 Jim Wallace of the Australian Christian Lobby tweeted: “Just hope that as we remember Servicemen and women today we remember the Australia they fought for – wasn’t gay marriage and Islamic!”

He went on to defend the tweet by arguing that it was “a comment on the nature of the Australia [his father] had fought for, and the need to honour that in the way we preserve it into the future.”

Right.

So basically Wallace is arguing that just because soldiers fought and died in 1943, our country should feel compelled to uphold the values of 1943. You know, decades before homosexuality was decriminalised, back when the death penalty was in vogue, conscription was encouraged, there was no such thing as Invasion Day, and men were commonly excused for rape and beating their wives around a little behind closed doors. The views expressed by Wallace and his peers threaten to undermine the Anzac message, turning our national day of remembrance into an ageing jock-club; just another opportunity to reiterate a pre-approved narrative of war-centred nationalism and recapitulate the resoundingly masculine dominant Australian.

But here’s the real problem – Jim Wallace isn’t alone in his beliefs.

Christian Army Officer Bernard Gaynor went on a scathing online rant in 2014 after current Australian of the Year David Morrison suggested that our historical Anzac image of heteronormative larrikin-ism had become a double-edged sword, discouraging women and members of the LGBTIQ community from signing up to the military.

In response, Gaynor wrote:

“David Morrison is banging on again about queers in the Army because he doesn’t think that enough of them are signing up. (By the way, I only use the word ‘queer’ because the LGBT community loves to describe itself with this insulting language – even they have no respect whatsoever for their own perverse lifestyle).”

It’s messages like these which have allowed for Anzac Day to become the unfair scapegoat for a small-but-vocal minority’s bigotry and discrimination; working within a well-oiled governmental system which continually fails to acknowledge the less-ideal realities of this particular chapter in our nation’s history. It’s messages like these which suggest Anzac Day has become the vehicle by which the beliefs of Edwardian militarists are preserved and passed on to a new generation – a generation who, grounded in diversity, are starting to ask questions.

The reality is that Anzac Day is already facing the challenge of ongoing relevance in the face of a modern, multi-cultural and socially progressive Australia. In fact, reports commissioned in 2013 for the Department of Veteran Affairs preceding the centenary of Anzac identified “multiculturalism” as one issue to consider as a “potential area of divisiveness” during celebrations.

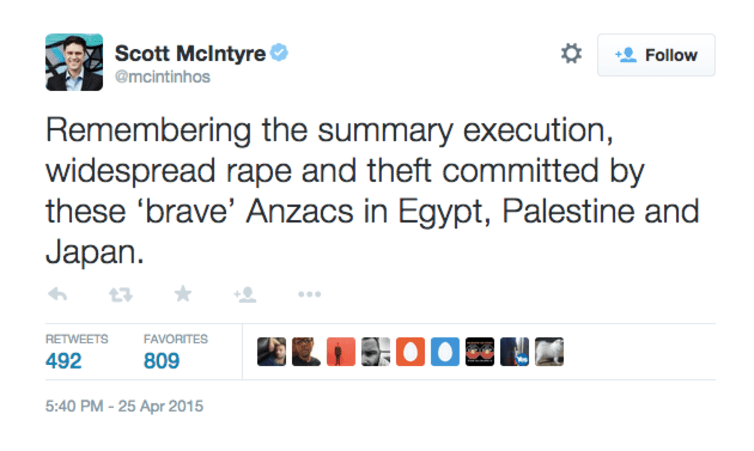

You see, those who dare express non-conformance to the traditional Anzac narrative are often persecuted on a national scale, as was made apparent by the firing of SBS journalist Scott McIntyre after he shared the following tweet last year:

Sure, the tweet was provocative, ill-timed and hugely insensitive to those honoring their loved ones, but I think perhaps it was indicative of a growing sense of unease at the implicit whiteness and heteronormative influence behind our national day of remembrance. Because when “we” as a nation remember, we simultaneously forget other important parts of the story. Anzac Day should never be used as the leverage for division or otherness. It shouldn’t be used as way of reinforcing our society’s countless hurtful misjudgements and discriminatory beliefs. If anything, it should be used simply to remember the thousands of lives cut prematurely short, and the senseless circumstances under which they served our country so bravely.

Sure, the tweet was provocative, ill-timed and hugely insensitive to those honoring their loved ones, but I think perhaps it was indicative of a growing sense of unease at the implicit whiteness and heteronormative influence behind our national day of remembrance. Because when “we” as a nation remember, we simultaneously forget other important parts of the story. Anzac Day should never be used as the leverage for division or otherness. It shouldn’t be used as way of reinforcing our society’s countless hurtful misjudgements and discriminatory beliefs. If anything, it should be used simply to remember the thousands of lives cut prematurely short, and the senseless circumstances under which they served our country so bravely.

If Anzac Day is to continue as a relevant day on the national calendar in a transforming society, and it undeniably should, I hope it can do so with renewed respect and honesty to the diversity of those both past and present.