How intersectionality is waking Australia up

By Charlie Tetiyevsky

Overpolicing and abuse of powers. A lack of affordable housing. Public safety for vis individuals. Extended offshore detention. Body acceptance. Gentrification. Rising homelessness rates. Attitudes towards mental health.

These issues are simultaneously becoming a concern to the LGBTQI community and Australian society at large not out of chance or coincidence, but because of the long trek to widespread acceptance of intersectionality.

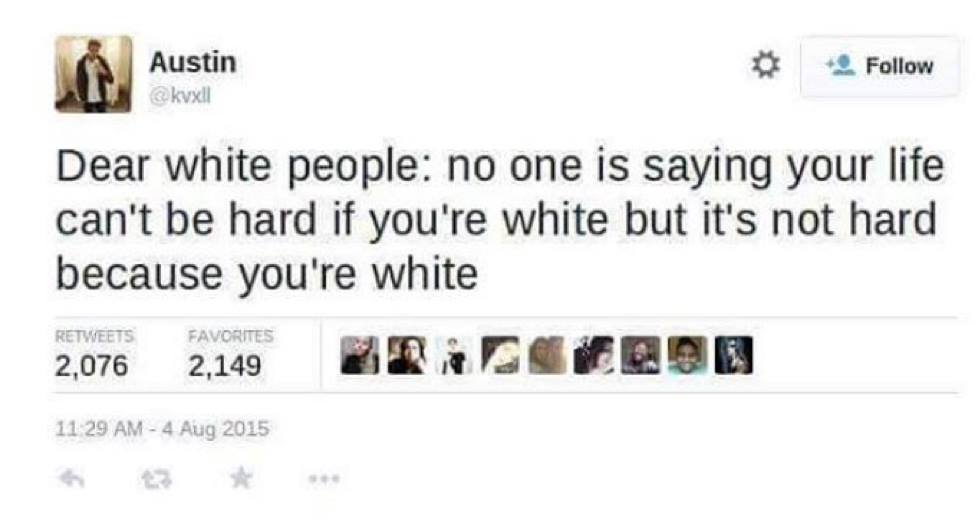

The idea of intersectionality—that social and public systems of oppression are all interrelated and connected—arose almost 60 years ago in the US in the quest to create a racially inclusive feminism. (This is where some folks might still argue that feminism isn’t exclusionary of people of colour and marginalised individuals: not always outwardly exclusionary, perhaps, but certainly even to this day most feminism pushes the experiences of those not in the majority—people of colour, transwomen, etc.—as being atypical and of secondary concern.) The general hostility against hearing the experiences of others within feminism and other non-minority-led left-leaning civil groups emerges because even such movements are often co-opted by the image of the “majority minority” (in this case the middle-of-the-road women—straight, femme, and white—considered to be the “default” in society) that acknowledges one marginalised quality/experience (mainstream womanhood) and one only.

The truth of the matter is that someone who is not a white or straight woman experiences the issues of being a woman in society at large and in their own cultural context (culture-specific attitudes towards being a femme queer and a butch one [not that those are the two only options but they’re often what being LGBTQI is reduced to] vary widely and are specific to those cultures) in addition to the experiences of biases arising from other parts of their identity.

We can address the similarities of our experiences in wider society as a jumping off point to discuss the differences, because those are the things from which we can really learn most. We should be discussing that on average, women make 17.3% less than their comparable male coworkers (and up to 30% less in the financial services sector). But in addition to that we also need to focus on the fact that there seems to be absolutely no discussion of a race wage gap compounding the gender one in Australia. There don’t even seem to be any statistics on the matter, but we can infer from the spread in America (arguably a society with almost identical attitudes towards race politics, despite what some people in both countries may like to think) that there is always a discrepancy among racial groups, putting certain women in categories that trend much lower-earning than other groups of women.

In the states, Hispanic women make the least money out of all recorded groups, so how is it possible to say that they have the same life experiences as members of the groups of women who make the most? We are all making far below what most men make, but gender is not the only determining factor and viewing it in isolation is to the detriment of fighting for all women.

Think about it as a math equation: it is not that a lesbian of colour is a lesbian and a person of colour (“lesbian + POC”). She is a lesbian in the context of being a person of colour (“lesbian of colour”), both things multiplied and amplified against one another to compound their complexity and effect on her life. We need to listen to these sorts of experiences because it complicates, and therefore strengthens, the integrity and structure of feminism. We need to recognise that experiences that differ from our own do not exist to fundamentally invalidate us; they are the actual things that other people go through daily. The act of pulling back on our viewpoints to try and recognise our own personal biases might be uncomfortable, but we can acknowledge and internalise how the systems of oppression that affect us can affect others differently without taking it personally—and if we can’t, it’s time to grow up and learn how.

Think about it as a math equation: it is not that a lesbian of colour is a lesbian and a person of colour (“lesbian + POC”). She is a lesbian in the context of being a person of colour (“lesbian of colour”), both things multiplied and amplified against one another to compound their complexity and effect on her life. We need to listen to these sorts of experiences because it complicates, and therefore strengthens, the integrity and structure of feminism. We need to recognise that experiences that differ from our own do not exist to fundamentally invalidate us; they are the actual things that other people go through daily. The act of pulling back on our viewpoints to try and recognise our own personal biases might be uncomfortable, but we can acknowledge and internalise how the systems of oppression that affect us can affect others differently without taking it personally—and if we can’t, it’s time to grow up and learn how.

Intersectionality may have originated as a discussion within feminism, but by its nature it has come to encompass the widespread social oppressions that have grown out of the dusty coughs of a dead, colonialist world. Western society has finally come to realise that the subjugation of a person by a system is not an isolated incident. If society displays institutional racism, what is the likelihood that they will respond fairly to other marginalised groups? What would be the motivation for that from the institution’s point of view? It doesn’t work for what it perceives to be people in “small” numbers; marginalised people are, well, marginalised despite the fact that one human’s life, one human’s experience, is just as important and valid and addressable as another’s.

Of course, it’s not easy to look at the mess that’s been built around us and take the responsibility of fixing it—the ultimate goal of all social movements. But we sweep up after a cyclone and we mop up after a landslide so that people can live a safe life after trauma—why wouldn’t we do the same thing about this mess of interwoven, biased social systems? If a place doesn’t care about black people, to paraphrase Kanye, what would make anyone expect that it would care about queer people, or non-neurotypicals, or those stuck in lower socioeconomic classes? If the motivating factor behind policy isn’t to provide a liveable and equitable life to individuals on the basis that they are people and deserving of respect, why does it exist?

These are not distinct issues. We cannot simply tackle homophobia or sexism, Islamophobia or Anti-Semitism, domestic homelessness or offshore detention—it is never one or the other. It’s a huge undertaking, but we must look at what connects and sustains repressive tendencies and do what we can as empathetic, social creatures to make our fight for justice a human one, and not just one for ourselves.

Saving ourselves means having to save us all, and we can only stay afloat if we raise each other up too.