“We were the first pinko, poofo, lesso, commie kids”

By Jonathan McBurnie

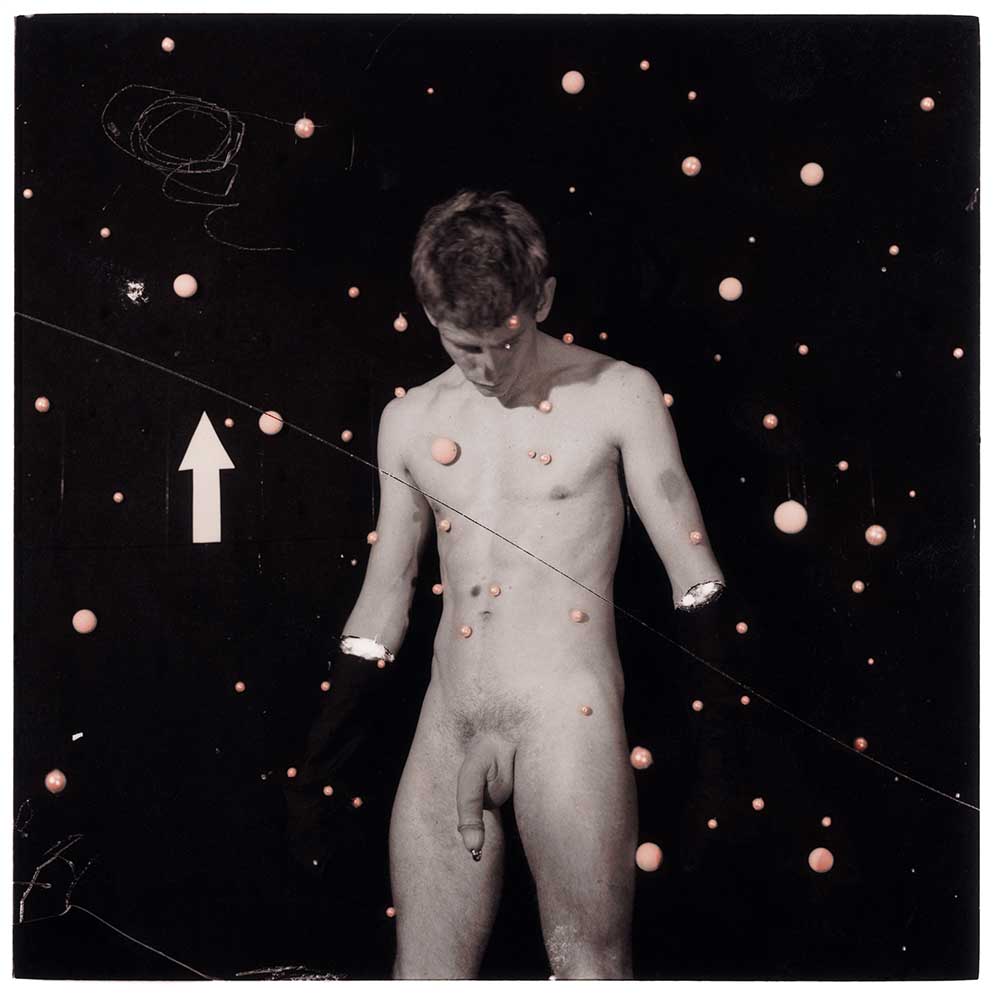

Ray Cook has been making and exhibiting photographs for the last three decades. In that time, Cook has seen queer culture shift from a radical and subversive movement to the mainstream, and the photograph morphing from the mysterious, obsidian blacks of the silver gelatin process to the pixelated gloss of the digital, and doesn’t like what he sees. Cook talks candidly with Jonathan McBurnie about HIV, mass culture, eroticism and mortality in his own honest and laconic fashion.

Your work has an ongoing dialogue with art history and the history of photography, which has gone through some rapid technological changes.

Technology (has) always been a driving force; it’s the medium of po-mo times. While a lot of old photographers take the digital revolution personally, feeling betrayed and superseded, every generation has seen the process they began with go obsolete. I’m okay with it because I can still use proper old processes. I think it’s wrong to unconditionally applaud technology. (It’s) always been a means by which capitalism alienates and dominates the population. Most of it’s bollocks anyway – your phone doesn’t need to do all that shit! With digital photography you pay heaps more for pictures that aren’t as good. The worst thing that is happening to photography is we believe in it less. The magic in a photograph is that whatever’s happened in it is real. A rudey-nudey photograph is way more naughty than a rudey-nudey painting. A photo of a disaster or violent act was more shocking than a painting. That magic is being eroded by digital jiggery-pokery. You need that implication of evidence to make a good tableaux photo work

Photography has an important relationship with eroticism, and has been an important medium in exploring and subverting notions of sexuality and gender. Do you approach these kinds of themes with any particular goal or intention?

Sexuality and gender were defining themes for my generation. We were among the first pinko, poofo, lezzo, commie kids that emerged out of a liberal education system that had been imperfect, but successful at discrediting old prejudices. Sexism and racism, and increasingly homophobia, were becoming uncool. The boys were forced to recognize – if not question – their privilege and the girls were demanding options. The taken-for-granted assumptions about gender and sexuality were being challenged. One of the reasons I started playing with art was the discrepancies I found between what everyone professed and expected about sexuality and gender and the reality. I wanted to demand a role in the construction of who I was. I didn’t want straight people, or other gays for that matter, to prescribe my identity. I might like blokes but that didn’t mean I had to like dance music. I never wanted to buy my identity ready to wear. I wanted to mix and match my own little ensemble, bits and pieces I’ve collected and put together myself. I suppose trying to reveal the way the mainstream uses expectations to control us is a recurring theme.

A lot of your imagery references theatre. This is completely out of step with a lot of contemporary photography which seems to be trying so hard to represent reality that it just gets painful. Documentary photography, photojournalism, reality TV… it shits me to to tears! What do you think of it?

There are few things more repugnant than reality TV. It carries all these god-awful narratives that endorse neoliberalism, normalizing the idea that the market is most effective distributer of fulfillment. It’s all about competition now. I hate sport, always have since I was a little kid… PE classes are a way to discipline boys to conform to poxy, one-dimensional forms of masculinity, and the whole thing shits me, but now everything I love is being turned into a fucking competition by reality television; music, food, it’s all sport now. And crying! That’s the new money shot. I burnt my soufflé, boohoo, I gained half a kilo, boohoo. I think they should do Biggest Loser the other way round, get the losers from Australia’s Next Top Model or the block and force feed them cream buns like French geese…

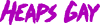

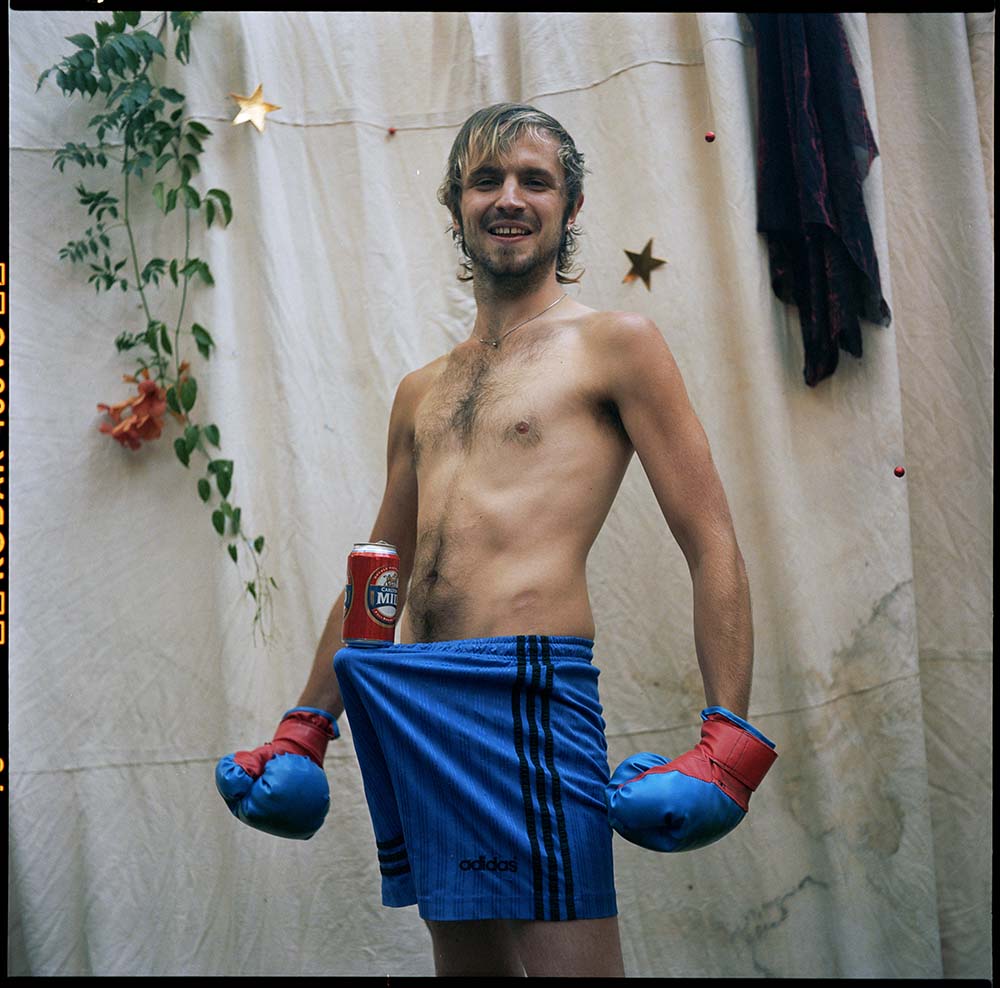

But I digress! Too often people assess photography on the basis of the criteria by which fine arts are assessed. The distinct things that are photography’s unique strengths, and so form the criteria against which it should be measured, are it’s state of continual flux. Technology keeps it moving. In its current form it’s not even anchored in material reality and it’s modes of distribution have become organic and unpredictable: no one can tell what image or representation will go viral (God I hate that term). Even though we know photography is subjective – and that it lies – we also want to believe it, and it’s the balance between fact and fiction that I find so compelling. The illusion of truth makes it a powerful tool for story telling. This faith we want to place in it is evaporating with digital practice. Photography is the language of advertising and governance and I increasingly distrust these things. (So) I think theatricality is often used to soften the evidential blow that a photograph carries. The alibi of fiction is a hoary old gay cultural chestnut. The early photographers saw no problem with photography being theatrical; it was only later when commercial possibilities for reportage emerged, with fast shutter speeds, that we developed the idea that a photograph should tell the ‘truth’. Tableaux or theatrical photography went underground and under acknowledged until pretty much the 80s, existing in pockets – advertising and pornography, for instance. Actually, gay male photography has continuously been theatrical, to protect the photographers and models from the consequences of real divulgence – especially back when we were outlaws and you could end up with jail sentences or lobotomies. Constructed photography seems huge now and perhaps it’s because technology has released us from those old modernist notions of truth.

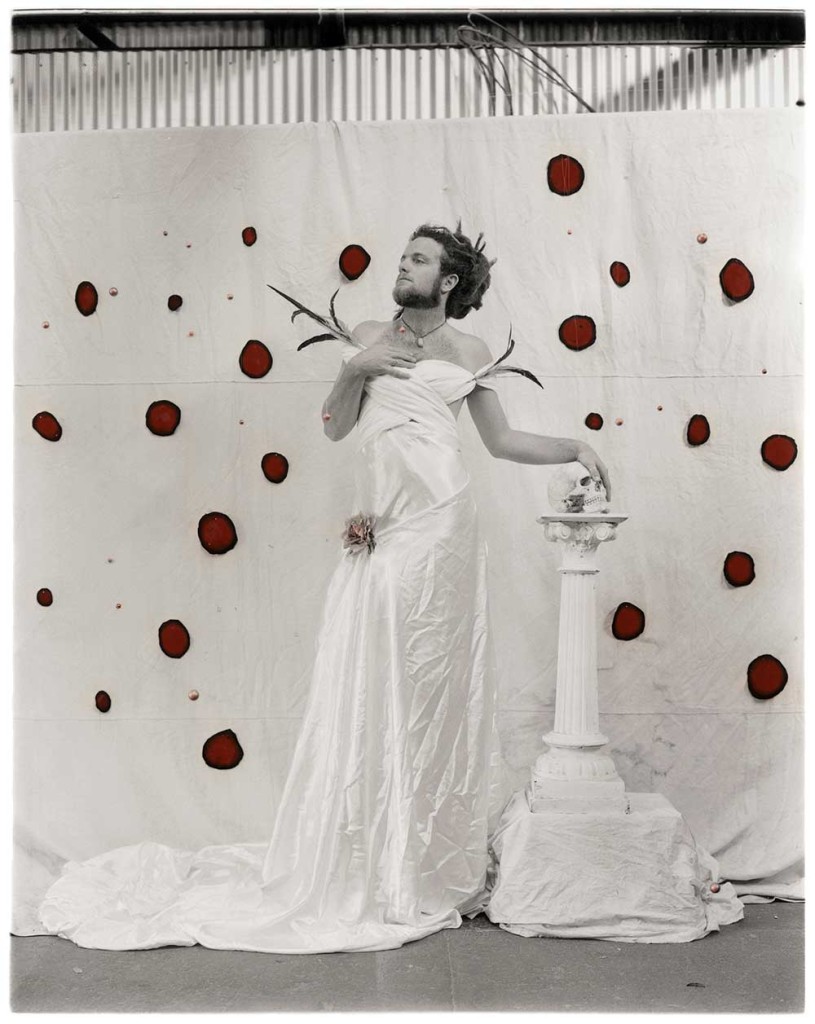

I have always felt your work has a humidity to it, and a masculine chemistry, which I associate with Queensland and specifically Brisbane. Blue singlets, cans of VB.

I love that! When I look back at my pictures I get a real Brisbane sort of feeling too. When I look at the pictures I remember the share houses, the parties and the people who were around at the time. A lot of my images were shot in the middle of parties. People would come over to our place to booze on before we all went out, so there would be groups of people in different areas. Under the house and in the back yard, some people tending BBQ’s, some getting dressed up, some watching sport on TV with no sound, some playing music. I’d just drag friends over to my area and we’d shoot things. It was a very Brisbane thing; all sorts of people together. I like specificity of place, (which) is becoming rare. A shopping centre is pretty much a shopping centre anywhere in the world now. Capitalism standardizes culture for the market. Identical McDonald’s franchises on every street corner, markets full of the same throwaway shit. You could go to any number of supposedly exotic countries and come back with the same singing fish wall hanging or panda shaped iPhone case. Capitalism prioritizes non-challenging, crap culture and it’s got a big loud voice. There’s great local creative culture out there but it just gets drowned out by Miley Cyrus or Paris Hilton. I once had an American gallery owner and supposed consultancy guru tell me that I shouldn’t have used VB cans because the wider market (read: American) might not know it was beer, or recognize the working class connotations. For me, the art I like reflects upon our experience of the world: it’s not the result of a careful marketing strategy.

Models have reappeared throughout your work, and some of them are friends. How does the relationship change and grow?

I’ve always sourced my models from my friends, always considered that I’m telling our story as much as my own. Their story is my story and vice versa, the universe entwined us. This has become a problem for me in some ways. We’re all grown up now, we have responsible jobs; we’ve made a place for ourselves in the world, we’re no longer the generation that thinks it’s funny to show your arsehole to a camera. No one wants to see my 50 year old willie waving in breeze anymore. For me and my friends a lot of my pictures are like a photo album, when we look through them together we don’t talk about their artistic merit, we talk about how much hair the people in them have lost or we wonder what happened to someone, where they are now, are they well… We remember life in the houses where the pictures were shot. I love that about them, that they have a secret meaning. Putting people I don’t know l in front of my camera feels weird: there’s not the familiarity that allowed me to ask things of my models.

There is a mortality, especially with the recurring characters. We see age over time – a bittersweet reminder of how life works. It’s a part of your work, but it doesn’t give in to pessimism either. I see occasional despair that is offset by a lot of laughter, love, lust and pathos…

I’m a poof who played around in the scene in the 80s and 90s and mortality is a huge concern for us. It still is, at least for those of us still standing. We all lost friends in our youth. It hasn’t stopped for that matter – words HIV or AIDS are (just) never mentioned anymore. I got HIV 25 years ago. Half that time I went to bed worrying about waking up sick, then treatments came, but I still woke up worried, this time about about growing old. Half the time scared of death; the other half scared of life. I’m still absolutely terrified of dying; I hate the idea of getting old! Creeping towards oblivion, towards the end, towards nothing, zippo, the big goose egg… It was people getting sick and dying in the 1980s that made me take art seriously. There was so much foreboding and anxiety – I had to find a release. While it seems like it must have been a grim time, there were fantastic parties. There were low points, sure, but there was a lot of fun to be had. I was always amazed how gay culture could find something absurd and hilarious in whatever fresh adversity we were served. It was actually really good to have the moral majority around as an enemy. It gave you someone to blame. It’s good fun to taunt fuckwits. You can’t offend anyone these days, which makes things a lot less fun. That’s one of the great values of camp; it turns humour into a shield. I think I’ve inherited a compulsion to make jokes out of serious things – something I learned from old queens in my youth. I still do it, I can’t seem to stop myself. It can be awkward at times.