Dancer Benjamin Hancock Transforms Our World in this Gorgeous Video Essay

By admin

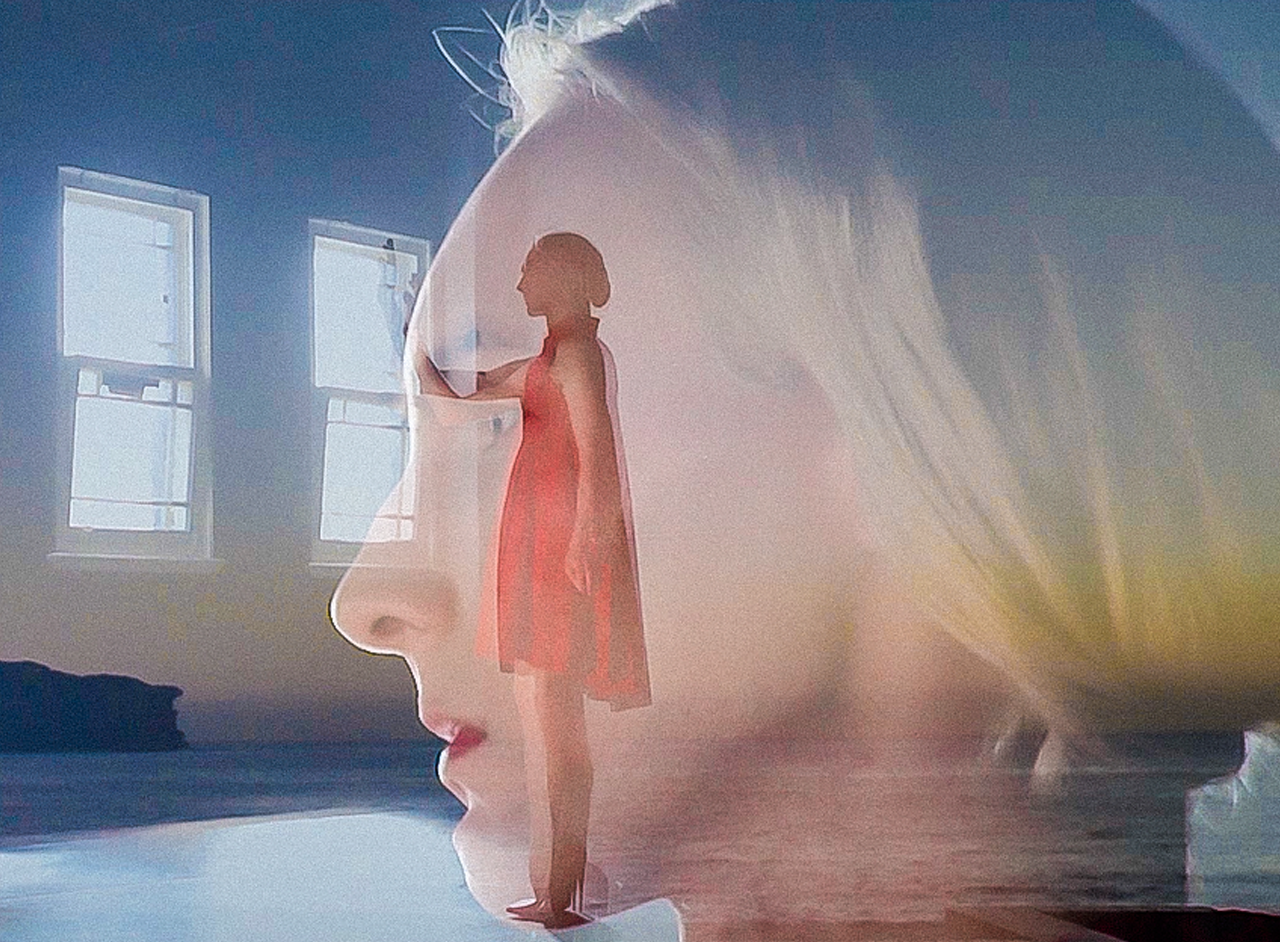

Benjamin Hancock’s vision in red rose from the flames of Sydney’s performance evening ‘Happy Hour!’ Curated by the exquisite Narelle Benjamin, this independent program provides a platform for new work developed in collaboration with three Australian artists each month.

Run out of Readymade Rehearsal Space in Ultimo – the gorgeously shadowed room in which Benjamin first appears in our film – the night is a delightful display of talent and transformation.

I arrive there on a Saturday evening to see Benjamin’s performance ahead of our early morning shoot. An outdoor spiral staircase funnels me up to a verandah where a group of vibrant people are waiting for the show to start.

The night opens with a film installation by Linda Luke and Martin Fox; a foreboding movement piece shot against the Australian outback at twilight. This shared interest in the relationship between place and performance proves affirming for Benjamin, who is already in the process of shifting his studio work into nature for our very own cinematic collaboration.

After the screening we move into a second room. Under the spotlight, Benjamin appears as a splash of colour in the darkness propped up by heels so high my reaction to them is visceral.

Music starts to play – a haunting song by Bat For Lashes – and Benjamin’s stillness casts a spell upon the room. His presence constantly shifts from something doll-like into drag performance with each subtle turn of his head and hands.

Benjamin’s violently red shoes remain rooted to the floor as he slowly descends towards it, his legs carrying conflicting connotations of fragility and sheer physical strength. He describes the ‘woman in red’ as a potent symbol.

“There is an idea of power, presence and independence inherent to red clothing, but on the flip side it can be objectifying.”

Benjamin’s work also plays with the scale of masculinity and femininity. Not to juxtapose binaries, but as a means of forging tension in how they overlap.

Ambling across a grassy knoll at Bronte Beach the next morning, Benjamin recalls an incident that occurred near a soccer field in North Melbourne. Ogled by a team of young men, Benjamin overheard one of them make a crude comment about his appearance.

“He’s so small, I feel sorry for him.”

Calmly, Benjamin proclaims a self-power that isn’t determined by masculinity.

“We all look unique and come across differently and I think that should be cherished.”

Indeed, what viewers interpret from Benjamin’s art says more about them than it does about him. I ask Benjamin about the red dress that seems so integral to the work we’re documenting. Designed by Steven Kalaia, Benjamin’s brief was specific.

“A thick fabric like an old stage curtain, a craziness in the pleat system so that when it moves around it has a different mode of existence than when standing still.”

In contrast, his striking stilettos reflect what is static about identity.

“High-heeled shoes were invented for men and women mostly of higher class for a sense of elevation and importance. Height of the heel also suggested the illusion of speed while suggesting the promise of an imminent fall.”

Despite this, Ben traverses time and space in the filmic adaption of this performance, posing questions about the transgressive potential of heels in a new context.

As part of performance collective YUMMY Benjamin is also a staple of the queer scene, frequently performing at parties in both Melbourne and Sydney. You might remember his recent appearance at Heaps Gay’s Pardi Gras where Benjamin crawled across the stage to throw a half-eaten carrot into the audience while lip-syncing to queer anthem ‘Feed the Horse’.

When I ask Benjamin if he choreographed that show, he explains that his dance practice is a mixture of anchored choreography and improvisation. Benjamin describes this approach as akin to a musician and their body of work.

“The theme, content and questions from each solo become the orchestration of each single and album.”

Benjamin’s movement is unique to every performance just as the singer’s voice is always recognisable, yet forever in flux.

After we wrap, Benjamin and I drive to Rozelle to check out a vintage store on Victoria Road. A family inside with two young children are eager to chat with Benjamin as he tries on clothes.

It turns out they’re from Melbourne, too. The parents, a lovely man and woman in their mid-thirties, are keen to compliment Benjamin on the green fur coat he’s chosen to buy. I smile, awe-struck by the the magical effect he has on people even out of costume.

Benjamin is against the mould, but he doesn’t affront the mainstream. Instead, his body language invites others to feel comfortable in expressing themselves just as he does.

As we leave the store, Benjamin interrupts my moaning about how early we got up to comment on how many men strike up similar conversations with him.

“They often say something like… I thought you were a chick, then I was like… Shit that’s a guy!”

Benjamin chuckles confidently.

“I’m not demanding or asking them to find sexual interest in me, but instead feeling an openness to question what is beautiful within my work. Being confused doesn’t make you less of a man.”

Pondering this (one of the many wise things Benjamin has told me) I realise he’s right. Being confused isn’t something to be ashamed of. It’s a space to make us open up and question each other and ourselves.

It’s what makes us human.