Carving out a Queer Space in Feminism

By Charlie Tetiyevsky

As an editor and publisher, I’ve long championed putting women first and creating artistic spaces where they are given precedence.

It’s important to provide not just a temporary nod through one-off “women’s” events (gallery shows, readings, festivals), but also dedicated spaces where women know they can come and make their thoughts heard and work seen. I loved—and love—womanhood and the sisterhood of femininity, especially in an age of growing intersectionality and at the shared ideal of eventual inclusivity. I am invigorated by being around women, and the sort of woken passion that I see in my sisters is one of the things that reliably brings warmth to my chest.

Compartmentalisation has always made me comfortable — landmarks in a lifetime of nonsense, places to look back on and point to as the origin points of things.

I remember the first time I touched a girl, the first time I was called “sir,” when I was recognised by an ineloquent, posing-as-vanilla queer philanderer as “a girl who likes to do guy things.” I remember the relief of being able to use the men’s room or the women’s room without being told off or made fun of, I remember wondering to myself as a child if I wanted a penis (love/hate you, strapons) and wondering as a teen if those thoughts made me a bad woman or feminist. I remember being disappointed that my androgynous body grew breasts in my early 20s, I remember not wanting to return to wearing dresses even though I finally had the hips for them, I remember being addressed by the gender neutral version of my name aloud for the first time.

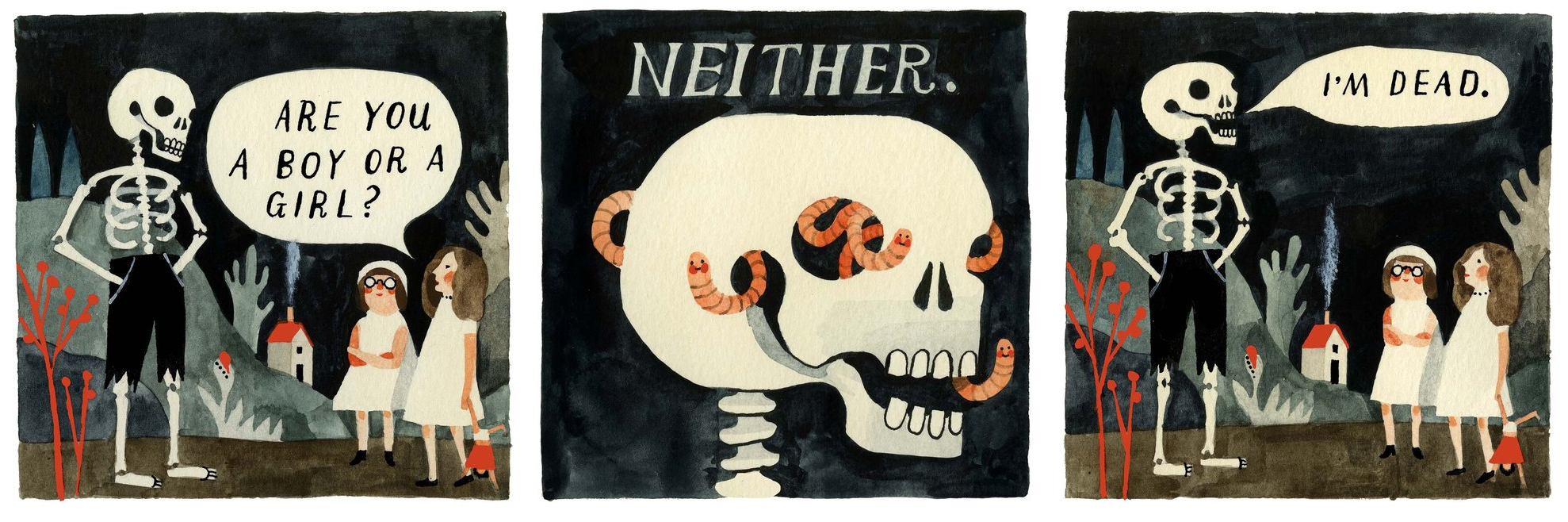

Identifying as something other than feminine — I made the aesthetic shift in my senior year of high school — was difficult when masculinity and manhood felt like they stood against everything I had always rallied for. I didn’t know a word for what was happening and had a hard time conceptualising what it was, exactly, that I wanted for myself and my body. Public school in the U.S. was the way it is portrayed in the movies—generally hostile to the Othered kids, certainly far away from any sort of LGBTQ-inclusive “safe school” (I wanted to start a chapter of the Gay/Straight Alliance but was rather strongly discouraged)—and so I didn’t even realise that there were words other than “male” and “female” that could describe what I was. I hadn’t heard of being trans or non-binary at home, or in the media, or in school, or from friends, or even online. I sort of dismissed the whole thought entirely (in retrospect, who hasn’t gone through a bit of closeted denial), ignoring how I felt internally because I didn’t want to abandon a kinship that I held dear.

When I shifted to being vis (before knowing what it was), I didn’t even really think that female “masculinity” (what I now realise is genderqueer and/or being non-binary) could be interpreted as an expression of internalised patriarchy. This is just how I look and act when I am peak me, and I’ve always been so hyper-conscious of oppressive gender structures that I was hurt hearing that I was seen by some women as buying into that hierarchy. I was saddened to think that it seemed like I was condemning traditional femininity as “weak” just by rejecting it for myself. I am a grrrl regardless of what I look like, and how I present myself does not have any effect or place any restrictions on anyone else.

The fact of the matter is that expressing as female or femme at any point in one’s life—either through being socialised female or transitioning from MTF — even if that identity has waffled back and forth, means that the person has had their own individual experience of being a woman/female. There are many different forms of womanhood, and many of these aren’t restrained to traditional cis-bodied, female-identifying individuals.

When transwomen and non-binary people are treated badly by the public in general it’s not just transphobia; it’s a reflection of how society sees the value of being female and femme. I recognise as a person who has progressed through being traditionally feminine to “butch/masculine” to genderqueer that there is simply no single “woman experience.” So many factors come into play—among them race, socioeconomic status, social safety nets—that discounting the experiences of our fellow feminists is only to our detriment as we seek to combat oppression. It’s important for us to validate one another in a world that tears down the women and queer people who challenge the existing gender dichotomy, or else we become the same as the people who want to silence us.

If you’re the sort of person who legitimises exclusionary spaces because, to quote Germaine Greer, someone can “lop off [their] dick and then wear a dress [but it] doesn’t make [them] a fucking woman,” then what place is there in feminism for people born female who no longer necessarily identifying as a traditional woman? Greer suggests that gender reassignment surgery is “actually inflicting an extraordinary act of violence” on the self, but then what would she think of genderqueers like me who like to bind their breasts? She says that she thinks that “intersex is an important state of life and should be allowed to exist”—what makes that different from people who have told me I shouldn’t exist in the way I do? Isn’t such thinking hostile, not only towards transwomen but also people who live as non-binary or untraditionally female? (Also, implying someone “shouldn’t be allowed to exist” is the first instance of casual 21st century eugenics I’ve ever encountered. Interesting considering that in the same interview Greer chooses to make the befuddling comment that she wishes she was Jewish but couldn’t be [for the record, Germaine, you can totally convert—or, you know, “transition”—to Judaism].)

I know that lots of genderqueer and non-binary people identify as trans; I personally don’t know yet if it’s my place to step into that conversation, but I still really find comfort in trans-friendly spaces because I know that I can exhale and feel safe and like someone will be receptive to what I have to say.

That’s the main issue: receptiveness.

How are we less strong as a feminist movement when we listen to those around us? When has being able to hear about the experiences of our peers been a detriment? Isn’t it our duty to protect people who fall or have fallen under the umbrella of womanhood and to recognise that until the marginal grrrls are treated properly, the mainstream won’t be either? Women (cis and trans alike, and particularly women of colour) spearheaded the movements for social and civil equality in the 20th century, and I have no reason to doubt that they will continue to step to the forefront of this sort of agitation for rights.

If we don’t do it no one will, and if no one does it we will never get anywhere near untangling the social trappings that bind us all.